|

|

|

MARKETS : Markets as communication systems

Assessing the performance of different market institutions using computer

simulations

Franck Galtier, Cirad.

The famous work by F. Hayek, L. Hurwicz, J. Stiglitz, and S. Grossman

showed that market performance depends on an ability to ensure the dissemination

of information between economic stakeholders. As information is passed

on by the processes of negotiation and trade, the type of trading network

plays a crucial role since it determines the architecture of the channels

through which information flows. Recent work has analysed this aspect

using mathematical tools (Kirman 1983; Ioannides 2002) or computer tools

(Kirman and Vriend 2000; Kerber and Saam 2001). The work described here

falls into the second category.

It involved a comparative analysis of the performance of two modes of

wholesale trade organization widely used in agricultural commodity chains

of the developing countries: network trading and marketplace trading.

Store of a wholesaler in Niono (Mali)

These two institutions function very differently. In the case of a trading

network, each wholesaler in a consumer zone (CW) has correspondents (PW)

in the different production zones (one per zone) and, in principle, should

only procure supplies from his correspondents. Thus, when a CW wishes

to buy maize or millet, he contacts his correspondents in different locations

(usually by telephone, or by mail delivered by truckers or taxi drivers),

centralizes the sale proposals made by each of them (in terms of price,

quality, delivery date, terms of payment, etc.) and enters into transactions

with the one making the most interesting bid. The entire process of negotiation

and exchange takes place at a distance. In the case of wholesale markets,

CWs circulate in the production zones, where they meet PWs in the marketplaces

(on market day). The dissemination of information is therefore very different

in the two types of institution.

Wholesale markets in Kétou (Bénin)

Wholesale markets in Kétou (Bénin)

Discussion on the relative performances of these two institutions has

major repercussions for public policies. Indeed, States and funding agencies

tend to favour wholesale markets, which are judged to be preferable for

ensuring market "transparency". It is this idea that we have

attempted to test here, by analysing whether any situations exist where

trading networks prove to be better communication systems than wholesale

markets.

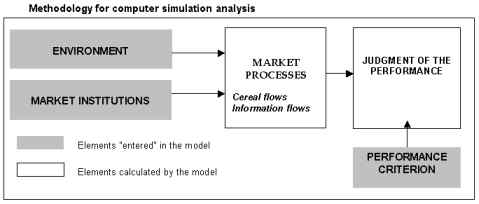

The

analysis was based on computer simulations using a multi-agent system

(MAS). The approach consisted in "entering" an (environment,

market institution) pair in the model, simulating the induced exchange

processes and measuring the efficacy of the resource allocation obtained

in that way (in accordance with a previously defined performance criterion).

This approach (shown in the following graph) makes it possible to test

the comparative efficacy of wholesale trading networks and wholesale markets

in different environments (to see their respective scope of relevance). The

analysis was based on computer simulations using a multi-agent system

(MAS). The approach consisted in "entering" an (environment,

market institution) pair in the model, simulating the induced exchange

processes and measuring the efficacy of the resource allocation obtained

in that way (in accordance with a previously defined performance criterion).

This approach (shown in the following graph) makes it possible to test

the comparative efficacy of wholesale trading networks and wholesale markets

in different environments (to see their respective scope of relevance).

In the scenarios performed, the environment was modelled from two

sets of variables: the degree to which the activity was concentrated on

the level of production zone wholesalers (PWs) and the variability in

supplies to those wholesalers. The market institutions represented

were trading networks and wholesale markets, along with an imaginary "perfect"

institution, i.e. one which enabled total market transparency and optimum

allocation of resources. This last institution was used as a control to

measure the efficiency of the other two. Lastly, the performance criterion

adopted was the minimization of rationing in consumption localities.

The simulations involved 150 different scenarios (50 environments and

3 market institutions). Each of the 150 scenarios was simulated over 100

time periods, approximately corresponding to two farming seasons, taking

a model time period to be a week in reality (numerous marketplaces operate

on a weekly basis). A thousand simulations were carried out for each scenario,

in order to neutralize the effect of the random variables introduced into

the model.

The main results were as follows :

- Whilst networks and wholesale markets disseminate far fewer bits of

information than the control institution, they manage to generate an

allocation of resources that is almost as good (at least when the environment

is unstable, which tallies with numerous true situations). This is confirmation

of the intuition of F. Hayek and L. Hurwicz whereby market institutions

that are relatively economical in terms of disseminating information

can lead to an efficient allocation of resources.

- The most decisive (environment) variable for the comparative performance

of the two institutions was the number of production zone wholesalers

(PWs). In fact, when there are 15 PWs, networks always prove to be more

efficient than wholesale markets, whereas the opposite is the case with

30 PWs. This result fits in with the empirical reality of the cereal

markets in Mali and Benin. Indeed, in Mali, the activity is highly concentrated

at PW level: there are only around ten per stockpiling locality. Conversely,

in Benin, this activity is covered by smaller scale PWs in larger numbers

(between 60 and 150 depending on the stockpiling localities). Yet it

is actually in Mali (where the PWs are larger scale and fewer in number)

that trading networks are found and in Benin (where PW activity is far

more scattered) that wholesale markets are found.

This result is contrary to the preconception whereby wholesale markets

are better communication systems than trading networks. This should logically

lead to a total rethink of public policies in this field (which are currently

geared towards promoting wholesale markets).

Computer modelling of market processes proved to be relevant in explaining

how an efficient allocation of resources can result from the decentralized

interactions of numerous individuals among whom the information is dispersed.

This approach thus complements other tools such as the games theory or

market experimentation [Smith 1982; Roth 2001]. Its strong points are

that it enables an analysis of market processes within which transactions

take place "out of balance" (which is difficult with the games

theory), and involves numerous stakeholders and quite long time periods

(which experiments do not allow).

This work also opens up a certain number of research prospects. One of

them consists in including elements related to the "language"

of the market institutions. Indeed, The messages (embodied in the purchase

and sale proposals of the players) are expressed according to rules that

define how the different trading parameters should be qualified (price,

quantity, quality, payment and delivery deadlines, and delivery site)

and how they should be negotiated. These rules (which constitute the "market

language") can also be assessed using computer simulations.

Bibliography

AMSELLE, J.-L. (1977). Les commerçants de la savane : histoire

et organisation sociale des Kooroko (Mali). Paris, Anthropos.

DEMBELE, N. et J. STAATZ (1989). Transparence des marchés céréaliers

et rôle de l'état: La mise en place d'un système d'information

des marchés au Mali. Séminaire European Seminar of Agricultural

Economists.

EGG, J., F. GALTIER, et E. GREGOIRE (1996). "Systèmes d'information

formels et informels - La régulation des marchés céréaliers

au Sahel." Cahiers des Sciences Humaines 32(4): 845-868.

GALTIER, F. (2002). "Eclatement et incomplétude de la théorie

des marchés" Economies et Sociétés (in press).

GROSSMAN, S. (1989). The Informational Role of Prices. Cambridge, MIT

Press

HAMADOU, S. (1997). Libéralisation du commerce des produits vivriers

au Niger et mode d'organisation des commerçants privés.

Les réseaux marchands dans le fonctionnement du système

de commercialisation des céréales. Economics PhD thesis,

Montpellier, ENSA.M.

HAYEK, F. (1945). "The Use of Knowledge in Society", American

Economic Review 35(4): 519-530.

HURWICZ, L. (1969). "Centralization and Decentralization in economic

systems - On the Concept and Possibility of Informational Decentralization",

American Economic Review 59: 513-524.

IOANNIDES, Y. (2002). "Topologies of Social Interactions", Departement

of economics, Tufts University.

KERBER, W. and N. SAAM (2001)."Competition as a Test of Hypotheses:

Simulation of Knowledge-generating Market Processes", Journal of

Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 4(3).

KIRMAN, A. (1983). "Communication in Markets: A Suggested Approach",

Economic Letters 12: 1-5.

KIRMAN, A. and N. J. VRIEND (2000). "Evolving Market Structure: An

ACE Model of Price Dispersion and Loyalty", Journal of Economic Dynamics

and Control (ACE Special Issue).

LAMBERT, A. et J. EGG (1994). "Commerce, réseaux et marchés

: l'approvisionnement en riz dans les pays de l'espace sénégambien."

Cahiers des Sciences Humaines 30: 229-254.

LE PAGE, C., F. BOUSQUET, et al. (2000). CORMAS: A multiagent simulation

toolkit to model natural and social dynamics at multiple scales. Workshop

"The ecology of scales", Wageningen (Netherlands).

ROTH, A. (2001). "The Economist as Engineer: Game Theory, Experimentation,

and Computation as Tools for Design Economics" Econometrica 70(4):

1341-1378.

SMITH, V. (1982). "Markets as economizers of information: experimental

examination of the "Hayek hypothesis", Economic Inquiry 20:

165-179.

For further information, contact the

author or download the model (Cormas2003): markets

References

...soon !

|

|